Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

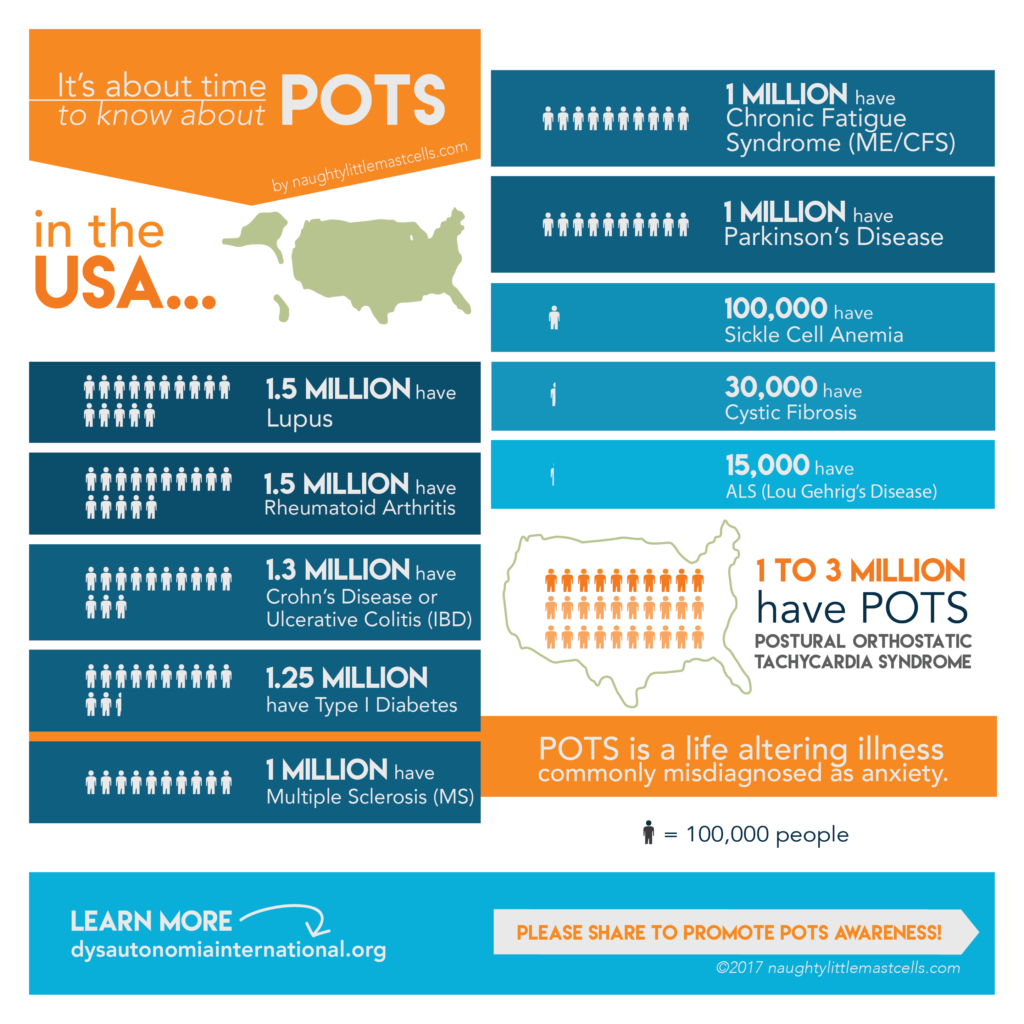

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is not a rare condition, but most people haven’t heard of it. This is likely because it’s a newer term (coined in 1993) for a condition that was deeply misunderstood since the 1800’s. 1 to 3 million Americans have POTS, and it’s conservatively estimated that there are over 10 million people with POTS worldwide. That’s on par with the population of Sweden! About half of POTS patients developed it in adulthood, and about 80% of POTS patients are female. An estimated 1 in 100 teenagers will develop POTS, and only a small lucky percentage will “grow out” of the symptoms. No one wants to be this 1%. Although POTS isn’t a terminal diagnosis, it can be debilitating and life altering. It can also be difficult for others to grasp because it’s an invisible illness- most of us still look fine if not great, but the struggle is very real.

How It’s Diagnosed

The diagnostic criteria for POTS is a heart rate increase of 30 beats per minute (bpm) or more, or over 120 bpm, within the first 10 minutes of standing, without orthostatic hypotension. (For children and adolescents, the heart rate criteria is raised to 40 bpm.) In POTS patients, blood pressure often drops when standing, but for others it actually rises. We’ve got strong hearts.

For official diagnosis, most doctors put you through a tilt table test, which is exactly what it sounds like. They put you on a table and tilt you varying degrees while measuring your heart rate and blood pressure. You can also do a quick test yourself or at any doctor’s office using a “poor person’s tilt test” method: Lay down for a few minutes, then take your heart rate and blood pressure. Next, stand up and measure your heart rate and blood pressure after 2, 5 and 10 minutes.

POTS is still often misdiagnosed as anxiety. Since POTS is a relatively new diagnosis, many established doctors are often misinformed or completely unaware of the condition.

Symptoms

Doctors use heart rate and blood pressure to define POTS, which is misleading because living with POTS means SO very much more. For most, it’s thought to be a partial dysautonomia of the autonomic nervous system… and when that nice automatic control system goes haywire, life gets hard.

Here is a list of the common symptoms…

Mental: Anxiety, Brain fog- difficulty concentrating & recalling words/facts/memories, Depression

Gastrointestinal: Nausea, Lack of appetite, Diarrhea, Constipation, Blood pressure and heart rate swings from eating/digesting

Dermatological: Pale skin, Purplish discoloration of skin in hands and feet due to blood pooling, Chronically dry skin, Feelings of pins and needles/shocks/tingling or numbness, Vibration sensitivity

Respiratory: Shortness of breath (easily winded)

Auditory: Sound sensitivity

Cardiovascular: Heart palpitations and high heart rate (worsened by upright posture), Fainting (syncope), Near-fainting, Lightheadedness, Dizziness, Difficulty sitting or standing (orthostatic intolerance), Graying-out upon standing, Raynaud’s phenomenon

A subset of patients have episodes of very high blood pressure. Some may also have episodes of low heart rate (bradycardia).

Vision: Light sensitivity (due to pupil dilation), Dry irritated eyes, Intolerance and sensitivity to contact lenses

Pain: Headaches, Migraines, Chest pain, Aching shoulder and neck pain (coat hanger pain)

Other: Fatigue & Exhaustion, Exercise intolerance, Shaking (tremulousness), Cold hands and feet, Frequent urination, General but strong sense of “feeling awful” or “feeling very wrong” without being able to point to any specific symptom, and more.

Some more details…

With POTS, your autonomic nervous system isn’t working properly (for reasons not yet fully understood). So, in a healthy person your blood vessels in your legs will constrict, to help push the blood up into the upper parts of your body, so staying conscious is easy. Whereas with POTS, your blood vessels don’t constrict as they should, causing blood pooling in your legs, so your heart pumps harder to compensate to maintain your blood pressure and to keep pushing an adequate blood supply up to your brain. This results in a higher heart rate, and the lightheadedness and exhaustion from standing (or even sitting).

Most POTS patients are also hypovolemic, meaning we have low blood volume. They’re not exactly sure why yet, but having low blood volume results in generally lower blood pressure, just making upright posture even harder.

Small Fiber Neuropathy

Also, many POTS patients have small fiber neuropathy affecting sudomotor nerve function, thereby affecting some autonomic functions.1 Some patients are further affected by small fiber neuropathy of sensory nerves responsible for thermal and pain senses, which can result in strange feelings of pins and needles, shocks, tingling or numbness usually in the feet, legs and hands. Or sensations can be more extreme, feeling like cold-like or burning pain. Something as simple as bedsheets can feel excruciating.

POTS, MCAS & EDS- A common triad

The medical community is finding that POTS, MCAS (mast cell activation syndrome), and EDS (Ehler’s Danlos syndrome) are often found together as a triad in patients.2 Again, the reason is unknown, but these three syndromes are probably inter-related in some way, there may be some common pathogenesis of some kind. If so, this may explain why many POTS patients are benefiting from mast cell targeting drugs even when they don’t present with obvious mast cell activation symptoms or aren’t testing positive for a mast cell disorder. EDS is a connective tissue disorder primarily marked by excessive laxity and flexibility of skin and joints. Even if a patient doesn’t meet the criteria for “full-blown” EDS, they quite often do have some joint hypermobility such as finger or elbow joints that hyper-extend.

Common Triggers

These common triggers can make symptoms much worse.

- Hot, warm or cold temperatures

- Exercise and modest physical exertion

- Dehydration

- Deconditioning & bedrest

- Common colds or viruses

- Periods & hormone changes

- Emotional and physical stress

- Scents and Odors

- Alcohol

Treatment Options

See a large selection of treatment options I’ve heard of, many of which I’ve tried myself…

What’s it really like to have POTS?

Yes, this all sounds awful, and the point is that it can be. There is no cure yet, but there is exciting research happening, and many treatment options. You grieve, you adapt and you persist! Your health might even improve over time…

Quality of life assessments show that living with POTS can be like living with congestive heart failure or dialysis for kidney failure. You may look totally normal, but every-day life is challenging.

- Chronically fatigued. Exerting yourself can leave you (in no exaggeration) exhausted for days afterward. For some, exertion means just trying to walk around the house, for others it might be what looks like a light workout on a reclined bike.

- No fun standing around. Just standing at a store checkout can become forced and difficult, because blood pools in your legs. You feel lightheaded and dizzy. If you start to feel faint, you might need to sit or lay down. At least walking moves your leg muscles to naturally help push blood back up the legs. Standing can be paradoxically tougher to endure.

- No shower relaxation. Simple things like taking a shower can make you lightheaded and exhausted. The warm water and steam naturally dilates blood vessels, again causing blood to pool even more than it already is, thus making your heart’s job even harder. It can kind of feel like sprinting in place.

- No more warm weather. Being in warm or cold temperatures can be difficult, making many symptoms worse. Forget basking in the hot summer sun on a beach. Even forget leisurely shopping in warm store. Something seemingly simple like walking through a hot parking lot to a store becomes a scary challenge.

- Like dementia. You might feel like you have dementia when you have brain fog. Recall is slow… kind of like how it feels to think when you’re insanely tired at the end of an all-nighter. It’s that bad.

- You miss your appetite. One of life’s simple pleasures is now elusive. You might have to think about what you can get yourself to eat that’ll keep up your calories. Even without the nausea, a lot of times food just sounds awful. Good chance you dread the dizziness and heart palpitations you get from blood diverting to your stomach for digestion. Normal people have no problems eating a snack, let alone a huge meal.

- You’re less reliable. Some days may be drastically better or worse than others, often times for no knowable reason. It can literally be a change in the weather, since many of us are sensitive to barometric pressure fluctuations. This makes planning social and professional engagements a huge challenge, if not impossible. Can you make that presentation? Can you even make it to the movies or that coffee joint? Having an unreliable body changes and strains almost all your social relationships. Your true friends and family will adjust and help, and others will fall away from your life. You experience loss, anger, and maybe even shame.

- You lose your active hobbies. Most of us were active, busy people before this thing overtook us. You probably can’t do all the things you used to. No hours of surfing or jogging. The activities you do keep require extra care, caution, medication, are much shorter in duration, and can leave you with little energy for anything else.

- Anxiety for attacks. Going anywhere can cause anxiety. You probably battle a justified and logical anxiety, and constantly plan the worst case. Trying to be safe is a struggle. Do I have enough water? Do I have all my emergency meds? Where’s the closest ER/Urgent Care? Where are the bathrooms? Will I be safe if I need to lay down and be ill? These are not the questions of a hypochondriac. Knowing these things makes you safer. Attacks happen and can’t be reliably prevented at all times. They come on quickly, with little to no time to get out of a store or social situation. You can reduce your exposure to triggers, but many times there won’t be an obvious trigger or any observable reason. Each POTSie has their own specific version of an attack and can vary in severity even for the same person. We all have them. The unpredictability of them amplifies their awfulness.

- …Then having an attack. You experience attacks that are scary and incredibly socially awkward. My scary but not uncommon attacks involve my heart rate shooting up, which comes with a sense of doom in itself. Then, feeling a wave of dizziness, I start shaking, shivering and chattering uncontrollably. I know this means to lay down ASAP or my body will pass out and do it for me. Sometimes there’s nausea and vomiting. I often feel the overwhelming need to empty my bladder, then maybe my bowels. How am I supposed to use the toilet when I can’t even stand? I take emergency meds, sometimes I can get there myself, sometimes I get carried by a loved one, and at my absolute worst- bedpans like a 90-year-old (in private thank sweet baby goodness). I feel like I’m dying, except I never do. I wish I could cry to release the wave of fear and panic that floods my brain, but my body seems to expending all its energy in keeping me conscious and alive. Emotions are free to overwhelm me once my body stabilizes. Paradoxically, once I’m crying I feel safe, with the worst behind me.

- Losing or downgrading your career. Working a full-time job can be hard, if not impossible. You may have to reduce your work schedule and lose career advancement, if not let go of your career entirely. And if you’re lucky enough to keep your career, you’ll probably be working MUCH harder than those healthy counterparts around you. I had to leave my full-time job as a professional mechanical engineer, creating a huge loss of financial independence and identity. Thankfully I can manage part-time work from home. Though the severity of the condition varies person-to-person, about 25% of POTS patients are officially disabled and unable to work. How would you be able to work if you had massive brain fog, fatigue, persistent nausea and difficulty sitting up? Healthy people having a taste of this would call in for a sick day and get to the hospital. This is how many POTS patients feel every day of their lives.

THE GOOD NEWS!

Each day isn’t always awful. You can have some good or even great days (all things considered). These symptoms can wax and wane day-to-day and over long periods of time. You can trend better. The symptoms and severity of them varies by person. And for many people, symptoms can be managed well by finding the right treatments. See a hefty list of treatment options on my Summary of Everything.

References:

1. Small-fiber neuropathy with cardiac denervation in postural tachycardia syndrome. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24647968

2. A New Disease Cluster: Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(14)02927-3/fulltext

Postural tachycardia syndrome – Diagnosis, physiology, and prognosis: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1566070217303545

Vanderbilt Autonomic Dysfunction Center- POTS: https://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/root/vumc.php?site=adc&doc=38847

Dysautonomia International- POTS: http://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/page.php?ID=30

Diagnosis and Treatment of Pain in Small Fiber Neuropathy: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3086960/